A newly discovered technique makes it possible to create a whole new array of plastics with metallic or even superconducting properties.

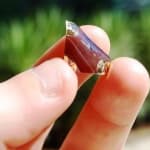

A newly discovered technique makes it possible to create a whole new array of plastics with metallic or even superconducting properties.Plastics usually conduct electricity so poorly that they are used to insulate electric cables but, by placing a thin film of metal onto a plastic sheet and mixing it into the polymer surface with an ion beam, Australian researchers have shown that the method can be used to make cheap, strong, flexible and conductive plastic films.

The research has been published in the journal ChemPhysChem by a team led by Professor Paul Meredith and Associate Professor Ben Powell, and Associate Professor Adam Micolich of the The University of New South Wales. This latest discovery reports experiments by former UQ Ph.D. student, Dr Andrew Stephenson.

Ion beam techniques are widely used in the microelectronics industry to tailor the conductivity of semiconductors such as silicon, but attempts to adapt this process to plastic films have been made since the 1980s with only limited success – until now.

"What the team has been able to do here is use an ion beam to tune the properties of a plastic film so that it conducts electricity like the metals used in the electrical wires themselves, and even to act as a superconductor and pass electric current without resistance if cooled to low enough temperature," says Professor Meredith.

To demonstrate a potential application of this new material, the team produced electrical resistance thermometers that meet industrial standards. Tested against an industry standard platinum resistance thermometer, it had comparable or even superior accuracy.

"This material is so interesting because we can take all the desirable aspects of polymers - such as mechanical flexibility, robustness and low cost - and into the mix add good electrical conductivity, something not normally associated with plastics," says Professor Micolich. "It opens new avenues to making plastic electronics."

Andrew Stephenson says the most exciting part about the discovery is how precisely the film’s ability to conduct or resist the flow of electrical current can be tuned. It opens up a very broad potential for useful applications.

"In fact, we can vary the electrical resistivity over 10 orders of magnitude – put simply, that means we have ten billion options to adjust the recipe when we're making the plastic film. In theory, we can make plastics that conduct no electricity at all or as well as metals do – and everything in between,” Dr Stephenson says.

These new materials can be easily produced with equipment commonly used in the microelectronics industry and are vastly more tolerant of exposure to oxygen compared to standard semiconducting polymers.

Combined, these advantages may give ion beam processed polymer films a bright future in the on-going development of soft materials for plastic electronics applications – a fusion between current and next generation technology, the researchers say.