Using smarter plastics, making them last longer and designing for the future, also in aesthetic terms, with end-of-life in mind. These could be the main precepts defining the role that the world of design can shape for itself in the coming years, forming the basis of an attempt to bring about the cultural change needed to limit the social and environmental impacts of irresponsible plastic consumption.

How design can tackle the plastics crisis

Of course, design alone can’t solve the problem, given the immense consequences of myopic industrial decision-making and inadequate recovery and recycling policies. Of the 90 billion tonnes of raw materials (minerals, fossil fuels, metals and biomass) consumed worldwide each year, only 9 per cent is reused, and in Europe less than a tenth of the 50 million tonnes of plastic produced each year is introduced into a circular economy model.

Yet design can achieve a lot in terms of improving quality by spearheading innovative projects that privilege eco-conscious materials, question their environmental value and encourage adopting new attitudes towards daily consumption.

Suggesting new behaviours

The ability to bring about new behavioural trends has always been central to the discipline of design, often beginning with the use of new materials, like plastics were in the 1960s. In 1964, when Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper designed the first ever children’s chair made entirely out of polyethylene – the most common type of plastic – for Italian furniture brand Kartell, the material still needed to build its credibility and reputation. An intelligent and sturdy design based on a single material resulted in an item so well-built that it remained in the company’s catalogue for over twenty years (going out of production only following a change in children’s physical dimensions): the chair has been passed down for generations and is still found in people’s homes today, fifty years on.

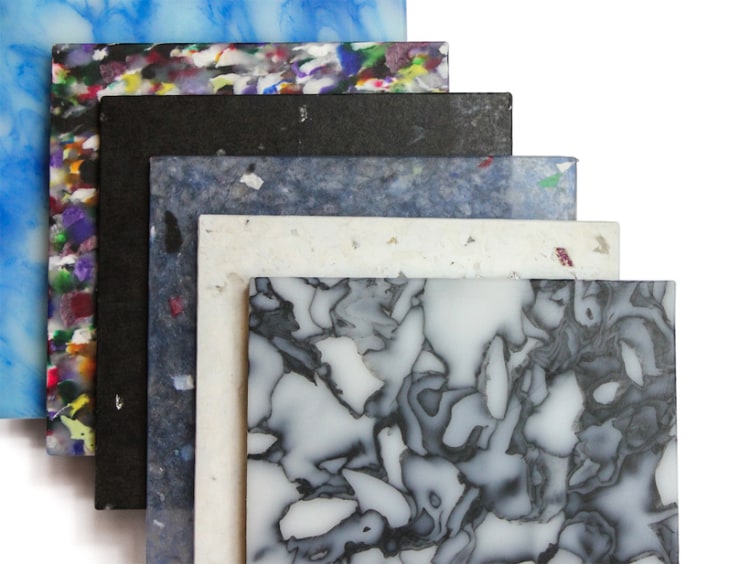

A sample from the Smile Plastics collection by Studio Smile designers Adam Fairweather and Rosalie McMillan. The studio offers a small selection of lifestyle products made from recycled plastics © Smile Plastics

Design’s response to the environmental catastrophe caused by plastics is still focused on the realm of behaviour, although today it aims first and foremost to give these materials some social dignity back, so that we may become more conscientious of our choices. This is part of a wider phenomenon that doesn’t only involve plastics. Daphne Stylianou, design researcher and past associate at Material Driven, British platform where designers and startups can showcase their innovations in this field, has coined the term “anthropology of materials” to describe the ever-growing attention that the design community is paying to their social role. This relates to their ability to influence people’s behaviours by promoting a higher degree of care and respect, as opposed to the lack of dignity we usually ascribe to everyday objects.

Conferring value to circular plastics

Across Europe, a growing number of innovative projects concerning materials design are finding new and sustainable possibilities for plastics, with the goal of transforming volumes of discarded waste into aesthetic materials, and integrating bioplastics into design strategies for the production of long-lasting products. On both these fronts, the driving motive is the production of beauty supported by the belief that design materials can become ambassadors of the value of conscientious product choices.

Ecothylene is produced by ecoBirdy. It’s more than just a technique for the selection, cleaning and recycling of plastic waste: the process on which it’s based separates old plastic toys by colour, thus leading to a higher aesthetic potential for upcycled products

Young designers are the ones driving this kind of experimentation, often independently, and by joining forces with engineers and companies, they’re producing materials using semi-industrial techniques. Many are derived from the processing of mixed waste that hasn’t been recovered through industrial or public recycling systems, bought locally and reworked, virtually by hand, to be sold online – sustaining a new upcycling alphabet through which recycled materials are transformed into higher-value objects.

Ecothylene by ecoBirdy

The most recent and probably most interesting of these ventures is ecothylene, a recycled plastic developed by ecoBirdy in Belgium. Its production begins with a process of waste separation based on colours (red, green, yellow, blue, white and clear), which allows for a high degree of control with regards to the resulting products’ aesthetics. The new material, presented in 2018 by ecoBirdy, the Antwerp-based company behind its development, has (for now) been used to create furniture for children: tables, chairs and containers, all pleasantly coloured and with an opalescent finish.

These products are beautiful regardless of the fact that they’re eco-friendly, and they have an important story to tell. The raw materials come from used plastic toys, which, instead of becoming waste, are recovered through an awareness campaign conducted in schools aimed at informing children on the issue of plastic waste and possible solutions. Subsequently, containers are provided to schools, and children and their parents are asked to collect used or broken toys that would otherwise be thrown away. The project, which uses waste from across Europe, is co-financed by the EU’s Competitiveness of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (COSME) programme.

The ecothylene project is part of a wide range of schemes that attempt to enhance the value of waste products that wouldn’t otherwise enter waste reduction programmes, giving them a new life.